qsSAXSI

Synchrotron quantitative scanning-SAXS imaging

This project goes back to my PhD (2000-04) on the development of synchrotron X-ray scattering analysis for nanoscale structural studies of materials at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) under supervision of Christian Riekel. The imaging aspect was started during my postdoc at the Max-Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces (2004-06), under supervision of Oskar Paris and Peter Fratzl. The theoretical and experimental developments involved many people over time, but the most important are Manfred Burghammer (ID13, ESRF), Oliver Bunk (SLS, PSI) and Jean Doucet (LPS, Orsay) who supported my CNRS project.

Keywords: X-ray scattering, SAXS, WAXS, Synchrotron radiation, Imaging, scanning-X-ray imaging, qsSAXSI.

The aim is to develop a quantitative imaging method to map nanoscale structural components in materials using small-angle X-ray scattering contrast .

In simple terms

All biological materials and many synthetic ones are built from well-identifiable nanoscale building blocks. Understanding how those building blocks are organized over multiple length scales is key to deciphering how those materials achieve exceptional properties. This strongly resonates, for example, in the fields of biomineralization, bio-inspired materials design, and nanomedicine. Nanoscale imaging and analysis is therefore an extremely important aspect for such matters.

The main problem when zooming in at the nanoscale, is that the information is obtained within a very small region, typically some tens of square microns. This is fine for homogeneous materials, but all biological materials are intrinsically heterogeneous, so what you see in a microscopic region might be very different from a neighbouring one. Since nanoscale imaging require relatively sophisticated instruments, repeating measurements can become extremely costly and burdensome.

An interesting alternative to nanoscale imaging is to use structural analysis methods such as spectroscopy, scattering, diffraction etc. The main difference is that with imaging, you actually “see” the atoms or nano-objects of interest, while other methods provide indirect structural information resulting from the physical interaction between the probe and the object. Using photons, electrons, neutrons (amongst others) allows acquiring information on atoms or molecules structure and their collective organization. By mapping, one can therefore derive images of structural parameters of interest over much larger regions than those accessible with standard nanoscale imaging.

More precisely

A detailed account of the qsSAXSI method applied to bone studies can be found in this book chapter: (Wagermaier et al., 2013)

In brief, X-ray scattering arises from the presence of nanoscale inhomogeneities such as pores, inclusions, interphases, etc., and is therefore widely used in materials science. The intensity of the scattered signal is directly proportional to the electron density contrast between the matrix and inhomoteneities, but remains with low probability (typically a few percent of the incident beam). So X-ray scattering studies strongly benefit from very bright synchrotron sources which are typically 3 to 9 orders of magnitude more intense. Synchrotrons also allow tunning the X-ray wavelength (and thus the energy) and efficient beam focusing, which is essential for mapping.

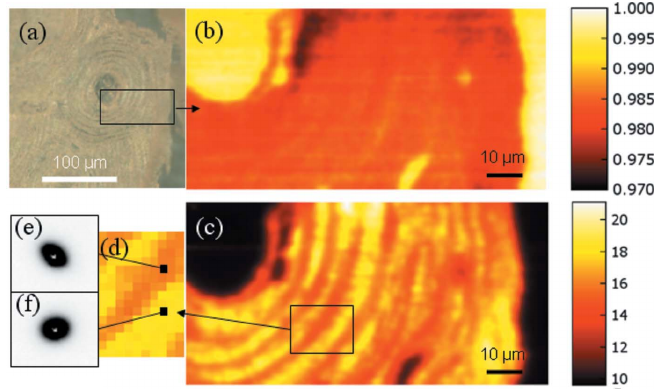

Scanning X-ray scattering measurements involve recording the 2D scattered signal by an X-ray microbeam as a function of 2D scan position. Each 2D scattering patterns is analyzed to extract scalar values to form 2D structural maps, i.e. parametric images. So my contribution to the field was essentially to develop efficient data reduction or analysis strategies.

The general problem with X-ray scattering, is that the measured signal is proportional to the square-Fourier transform (FT) of the electron density contrast. The “square” means that the phase is lost and only the modulus of the FT can be retrieved. This “phase problem” means that the FT cannot be mathematically inverted in a simple way, i.e. one cannot directly reconstruct the information without some a priori information. So Small-Angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) data analysis can be performed in two ways: either by extracting generic parameters assuming very simple approximations, e.g. biphasic material, dilute suspension of nano-objects etc., or by fitting a relatively precise structural model. The second case is therefore very case-specific and should rely on other types of measurements providing sufficient clues to what the model should be (although this sounds obvious, this is not always the case…).

My work on qsSAXSI was mainly focused on bone and other mineralized tissue as well as biominerals. So only those will be discussed here, although part of the methods could be extended to other very different materials.

First, we showed that images of the integrated scattered intensity (similar to what would be recorded using a photodiode - but not strictly equal though) of anisotripic nano-objects (e.g. mineral nanoparticles in bone) contains orientation information that can be quantified under certain assumptions (Gourrier et al., 2007). This allows visualizing differences in collagen/mineral orientataion in osteonal bone and was used to show that micro-elasticity fluctuations detected with GHz acoustic microscopy are mainly determined by collagen/mineral orientation - and not so much by mineral nanocrystal size (Granke et al., 2013). This is an example based on the use of integral SAXS parameters which only rely on the assumption that the material is biphasic and was therefore shown to also work on as diverse materials as egg-shells or even hair (Gourrier et al., 2007).

Second, I worked on refining a 1D stack-of-cards model to fit the radial SAXS profile which was initially proposed by Peter Fratzl. This model allowed better quantifying changes in the size and organization of mineral nanoparticles in bone in a case of Skeletal Fluorosis (Gourrier et al., 2010) and confirmed that bone formed during NaF treatment is strongly disorganized at the tissue level, which is totally inefficient biomechanically speaking.

Those developments were used in a broad range of medical (Fratzl-Zelman et al., 2009), biomechanics (Groetsch et al., 2019; Groetsch et al., 2023) and even archaeological studies (Gourrier et al., 2017; Albéric et al., 2014).

References

2023

2019

2017

2014

2013

2010

2009

2007

- JACScanning X-ray imaging with small-angle scattering contrastJournal of Applied Crystallography, 2007