AI super-resolution imaging

Currently supported by a MIAI Cluster Chair 2025-29

This project started in 2021 in collaboration with Prof. David Rousseau from the University of Angers, France and Prof. Kathryn Grandfield from McMaster University, Canada. It was initially supported by a research grant of the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP). This allowed funding the PhD of Lauren Anderson (2022-25). It is currently supported by a Chair in Artificial Intelligence from the MIAI Cluster.

Keywords: Super-Resolution Models, Multimodal Geometric Generative AI, Image Quality Assessment, Multiscale Biomedical Imaging, Mineralized Tissues, Bones, Teeth, Biological Cellular Network.

The goal is to investigate how deep-learning super-resolution (SR) imaging models could perform more accurately and with lighter architectures when taking into account specific structure of the input images.

In simple terms

SR aims at retrieving high quality images from lower ones, e.g. from a poor quality microscope, telescope or even a simple camera. For this, supervised deep-learning SR models can be trained with pairs of images aquired at high and low resolutions. Once trained, you can feed your low resolution images into the model to improve it, as if it had been taken with a much fancier (and probably way more costly) device, at least in theory…

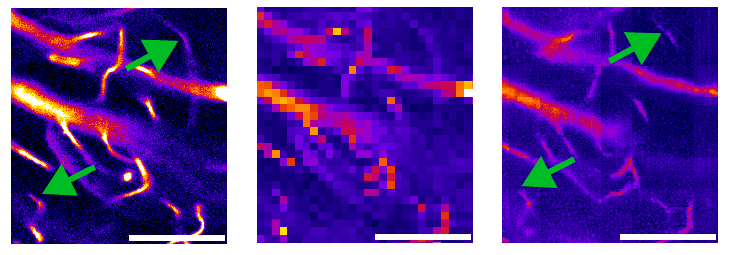

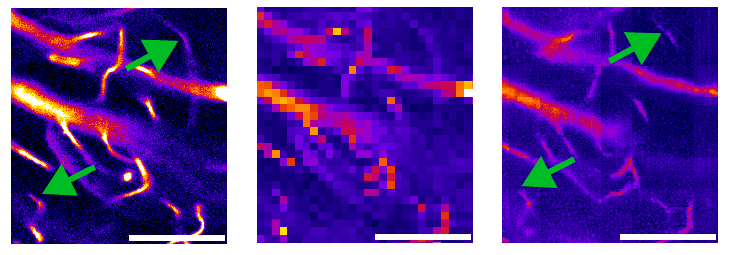

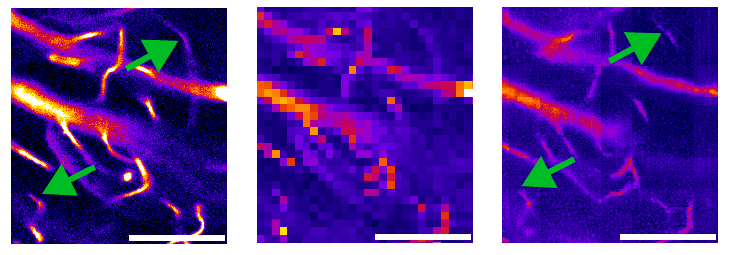

For example, the images below were acquired at different resolutions using a confocal microscope. Here the tested SR model can retrieve details even at x8 degradation, while our human eye can barely percieve the original high-resolution details !

SR models are typically built with some degree of mathematical logic, regardless of the type of images used for training - because they aim to be generic. See e.g. this review for more technical info. However, in many cases, the objects we image may, themselves, contain quite specific characteristics that could be used to improve existing SR models - at the cost of becoming less general. So the question is: how can we use such information to improve SR models ?

More precisely

Deep-learnign SR models fall in two broad categories depending on whether high- and low-resolution (HR/LR) input data are spatially correlated (paired) or not (unpaired). Paired models (e.g. Pix2Pix) generally require pixel-matched inputs of images, which can be experimentally challenging. Unpaired data aim to alleviate the need for paired input, at the cost of increasingly complex architectures (e.g. cycle-GANs). Those are known to be relatively unstable in training and require heavy hyper-parameter tunning. In summary, SR performance has increased over time at the cost of growing model complexity. There is, however, increasing evidence that informed models (e.g. physics-informed) may outperform others by design. In this chair, we propose to focus on specific applications of multiscale physical networks. The focus will be on microscopic cellular networks in bones and teeth, but our model should perform well on other types of physical networks, e.g. porosity networks in materials. Our goal is to develop geometry-aware SR models, which encode some features of the physical network topology.

Why is this important at all ?

Well, for one, costs: not everyone can afford the most expensive camera, telescope or microscope, for example. Imagine you could improve your own home-built telescope to the point where you could see imprints of the footsteps of the first guy who lay his foot on the moon ? Sure, there’s a big leap from here to there, but that’s the idea. The same goes for scientific imaging devices: SR models could allow better performance with simpler, less costly instruments. So there could be a tradeoff between hardware and software costs in a general sense (life-cycle, energy, environmental, societal, etc.).

Secondly, imaging accuracy: for example, even the most advanced medical X-ray CT scanners are often too limited to establish a precise diagnosis on bone fragility. Simply because of lack of resolution: we know that cortical porosity is a strong determinent of bone fragility, but CT scanners simply don’t have enough resolution (at best around 100 um for HR-pQCT, while < 10 um would be needed). But we can quantify cortical porosity very well ex vivo with lab instruments. So the question is: how much can push an SR model to improve X-ray CT (or any other modality) ?

Third comes the real motivations: it’s actually pretty interesting from a purely intellectual point of view ! I.e. how does an AI model get to do something that hard (see below) ? This implies that you actually understand the model - a.k.a. explainable AI - which means a big deal because now, we’re talking about getting new ideas… Also, if you reverse the idea, it is also very interesting to see whether a given SR architecture would perform better with your own expert input, rather than just performing “kind-of-randomly”. I.e. the model might perform better if it is “informed”. And, well, we have lots of ideas and knowledge in our lab to “inform” SR models ![]() .

.

Is AI really needed for this ?

A large part the chair members are originally experts in instrumental development and general image processing in computer vision. So we always put our efforts first into what we know best (and we believe this should always be the case): designing better images devices and processing tools. But 1) super-resolution can be a very, very, very complex problem because it combines too many challenges at the same time (see upcomming paper by Lauren Anderson); 2) the stakes are really high: according to WHO, 50 % women and 17 % men above 60 years old are at risk of osteoporosis, for example. And a large fraction of osteopenic fractures are still not explained ( more info ). This has huge societal, ecomical and political consequences !

So, yes, in this case, AI could make a real difference and, for now, there’s no simple way around. This being said, we are fully aware of the critiscisms around AI development and we are fully dedicated to taking all constraints into account. This means, in particular, developing light models to minimize computing hardware and energy resources, making our results widely accessible and facilitating technology transfer when possible.

So don’t hesitate to share interests and reach out at any time !